ALI article for Dzerkalo Tyzhnia

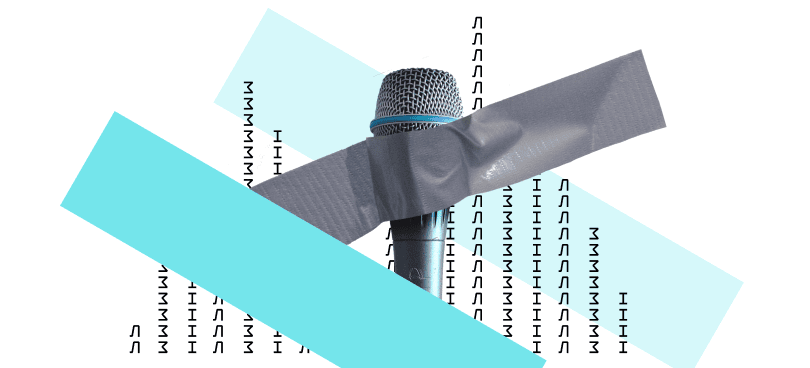

The biggest interrelated problems that the Ukrainian parliament has been suffering from for years include a large number of draft laws and their low quality. Thousands of draft laws (as of 29 January 2024, 6,277 of them were registered during the IX convocation), most initiated by MPs, have been accumulating in the Ukrainian parliament for years, draining the resources of the Verkhovna Rada. After all, the committees and expert analytical subdivisions of the parliament shall consider, work on, and provide conclusions on each draft law.

However, due to such a large number of registered draft laws, MPs suffer, too. After all, they find themselves in a paradoxical situation: on the one hand, they are required to make a decision, and on the other hand, the number of documents required for a balanced and reasoned judgement exceeds human capabilities.

In general, excessive workload reduces the effectiveness of the whole legislative process. Can this be changed?

How to limit “legislative spam”?

There are different approaches, such as reforming the requirements for accompanying documents. If the standards regarding compulsory accompanying documents to the draft law are changed, this will force the initiators to work more carefully on draft laws and enable the Verkhovna Rada to issue conclusions faster and with higher quality. There is progress here already: last year, the law “On Law-Making Activity” was adopted, which stipulates the reform of requirements for accompanying documents.

Another version of the changes, prescribed in the Roadmap by the European Parliament’s mission, proposes creating an exhaustive list of 20 priority draft laws that are being processed by the Verkhovna Rada. That is, MPs must choose 20 draft laws, which the Verkhovna Rada will process. Only after the draft law passes through the entire legislative cycle will another one be voted for at its place in the list. This will allow Verkhovna Rada to focus the resources on specific solutions and avoid the pressure created by the incredible backlog of draft laws to be considered.

Another way to address the problem consists in restricting the right of legislative initiative. Currently, every MP can register a draft law, regardless of its relevance and quality. Over time, the number of registered draft laws became a sort of indicator of effectiveness for the MPs. So, restricting the right of an individual legislative initiative looks like a logical solution to the problem. And they have already tried to do it several times.

For example, draft law No. 1311, “On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine Regarding the Exercise of the Right to Legislative Initiative,” was registered in 2014, setting this goal. The draft law’s path turned out to be short — it did not even reach a voting phase. However, the conclusion of the Verkhovna Rada Chief Scientific and Expert Department (CSED) is interesting: “The idea of refusing to submit draft laws by any MP of Ukraine deserves support.” According to their proposal, two changes are sufficient: 1) establishing the minimum number of MPs with the right to submit a draft law; 2) the possibility of registering a draft law of an individual MP in the event that such a draft law was developed at the request of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine and previously approved by the decision of the specialised committee.

Another idea was prescribed in draft law No. 6640 of 2017, “On Amendments to the Rules of Procedure of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. (Regarding the Letter of Support for Draft Laws).” It proposed to introduce two conditions for the continued work on the draft law after its registration: 1) support by a certain number of MPs, equal to the number of MPs of the smallest faction; 2) government support.

Both draft laws proposed a similar mechanism: legislative initiatives are developed only when they have the support of most MPs. It seems logical: if a relatively small number of MPs do not support the draft law registration at the basic stage, then the needed number of votes is unlikely to be found during voting in the session hall. Working on draft laws doomed to failure at the very start is a waste of the limited resources of the Verkhovna Rada and MPs.

Is it democratic and constitutional to restrict the right to the legislative initiative?

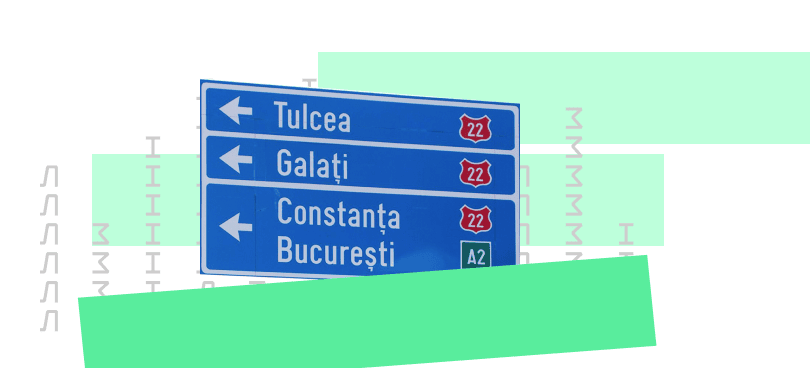

Collective legislative initiative is a common practice in many countries, particularly in Europe. As ALI mentioned in the concept of the legislative process, “from the beginning to the end,” “in Spain, this threshold makes 15 MPs for the lower house and 25 senators for the upper house. In Poland, the minimum number of MPs required to submit a draft law is fifteen; in Latvia, five MPs, and in Germany, the signatures of at least 15% of Bundestag MPs are required.” Therefore, it is difficult to equate the introduction of a collective legislative initiative with the moving of the Ukrainian state towards authoritarianism.

Many large-scale reforms are currently set aside until the post-war period because they require amendments to the Constitution. Can restriction on the legislative initiative contradict the Constitution?

Article 93 of the Constitution of Ukraine states that “the right of the legislative initiative in the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine belongs to the President of Ukraine, MPs of Ukraine and the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine.” Certain parliamentarians propose to interpret it literally: this right belongs only to the majority of MPs and not to each one individually. Also, the Constitution does not specifically establish what the “legislative initiative” is. It may be the legislative proposal (this norm also existed in the 1996 Rules of Procedure of the Verkhovna Rada), which requires support letters from a certain number of MPs.

However, some problems may arise with the implementation of these ideas. In fact, MPs already feel limited subjectivity, and even more restrictions on their rights may cause a negative reaction. At the same time, improving the quality and reducing the number of registered draft laws can positively influence their work because both the committees and individual MPs will need to make fewer decisions, which will translate into quality.

“Legislative spam” is deeply rooted in the Ukrainian parliamentary tradition. There is no simple solution to this problem, but a combination of measures can work: restricting the right of legislative initiative, strengthening the requirements concerning accompanying documents, and compiling a list of draft laws. MPs are aware of these issues and options for solving them. However, neither public pressure nor recommendations of the European partners can replace MPs’ work — they bear full responsibility for implementing these amendments.