The text was prepared for “Dzerkalo Tyzhnia” (Mirror of the Week newspaper)

The end of 2022 was remembered, among other things, for adopting the scandalous draft law No. 5655, which its critics were easy to call “urban rape reform”. Mass media wrote that it expanded developers’ capabilities, removing almost all responsibility from them while opening up new opportunities for corruption. The prospect of adoption made the public flare up: criticism was heard seemingly from everywhere: the Ministry of Culture, the Association of Ukrainian Cities, the National Union of Architects and many other public organizations, and even the NAPC came out categorically against the weakening of transparency in the field of construction.

Law draft No. 5655 gathered only 228 votes in its favour, with just three MPs providing the majority. A day before the vote, registered was a petition demanding to veto the draft law, which accumulated the required number of signatures in a few days. But time elapsed, and neither the veto nor the signature appeared on the document. All deadlines have passed, and No. 5655 still hangs in “legislative purgatory” as if the scandalous draft law had never existed. Yet thanks to that, another problem popped out, and it had been eroding the Ukrainian constitutional norms for years. What is happening, and how can it be addressed? We suggest you figure that out.

What is the problem?

Article 94 of the Constitution of Ukraine defines —“The President of Ukraine, within fifteen days after receiving the law, shall sign it, taking for pursuance, and officially promulgate it or shall return the law with his/her motivated and formulated proposals to the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine for reconsideration”.

And what if the President won’t do this? The same article states — “If the President of Ukraine does not return the law for reconsideration within the prescribed period, the law is considered to have been approved by the President of Ukraine and must be signed and officially promulgated”. In theory, we have a fairly complete picture of the adoption of draft laws. Regretfully, only in theory.

In practice, everything is a little more complicated. The thing is that the said norm does not provide a clear understanding of who must sign such a draft law if the “15 days of the President” have expired. On the one hand, this can be construed as meaning that the President him/herself must sign and promulgate the law (albeit in violation of the 15-day deadline). On the other hand, the very next paragraph prescribes a rule if the President vetoes the approved draft law and the Parliament overrides the veto with a constitutional majority of 300 votes or more: “If the President of Ukraine has not signed such a law, it shall be officially promulgated by the Speaker of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine immediately and shall be published with his/her signature”. Article 94 is contained in the very section of the Constitution dealing with the Verkhovna Rada.

All this gives reasons to believe that the draft law, which has not been signed by the president, must be signed by the Speaker of the Verkhovna Rada. One way or another, in the second case — when the veto is overcome (paragraph 4 of Article 94) —the directly approved entity is in place to take the last step for publishing the document. Whereas in the first case — when the draft law simply lies unsigned (paragraph 3 of Article 94) — there is no clear understanding of who exactly must sign the draft law that the President has not signed. This is what creates the most problems.

How was it used?

As history shows, it’s very simple: firstly, some Presidents allowed themselves to disregard the 15-day limit, and the fact of violation of the deadline has become a common phenomenon since Kuchma’s era. Subsequently, his successors used this increasingly more often: as of 26 June 2018, three dozen draft laws had been pending then-President Petro Poroshenko’s signature for more than a month. Gradually, lateness turned into nearly a habit — in the first two years of his term, Poroshenko, on average, vetoed the draft laws on the 19th day, thus violating the provisions of the Constitution.

Another very interesting thing happened during Petro Poroshenko’s tenure, the likes of which had not been recorded since the adoption of the Constitution — for the first time ever, a draft law was not signed as a matter of principle (the tenures for both the eighth convocation of the Verkhovna Rada and the fifth President have already expired). The draft law is still on the shelf at the Presidential Office. This refers to the infamous draft law No. 5553, which became a precedent for the abuse of the imprecision in the Constitution. It was aimed at reassuring the depositors of the newly nationalized Privatbank. At the same time, this document contradicted obligations to the IMF, possibly because the President did not turn to the draft law.

But the most crucial thing in this story is something else: never before had Article 94 been tested for strength so directly. It looks like this can be used in the future. This is exactly what is happening now: as of 10 April 2023, 25 unsigned draft laws sit and collect dust at the Presidential Office, with some of them waiting for their fate to be decided for years. For example, the draft Law On Amendments to the Budget Code of Ukraine No. 2661 of 20 December 2019 was submitted to the President for signature on 21 January 2020, i.e., more than three years have passed.

Specific trends in “very nearly laws” appear to be rather vague. However, even the existing picture, drawn with broad strokes, seems fanciful. Of the total number of “forgotten” documents, two were submitted as drafts by President Zelenskyi himself and three more — by Prime Minister Shmyhal. The case becomes even stranger considering that the initiators of another 18 draft laws included members of the pro-presidential parliamentary faction, Servant of the People. That is, out of the 25 ignored draft laws, 23 — the absolute majority, 92% (!) — were submitted by members of the ruling coalition or by “Zelenskyi’s people” (including himself, no matter how ironic this sounds).

Other data reveal a greater depth of the overall picture: 13 out of the 25 analysed draft laws were adopted by more than 300 votes — that is, the complete consolidation of the Parliament can be mentioned in their case. And when the President does not sign such draft laws, what we have is a “silent veto”, as it is called, which can’t be overcome. 52% of the draft laws already have a constitutional majority, so the subsequent evolution of the case can be imagined as follows: the President vetoes, and the Verkhovna Rada would have to overrule (of course, if he were to have the political will and once again collect 300 votes for such initiatives). Instead, the “silent veto” — ignoring a draft law submitted for signature — cannot be overcome at the moment.

So, three trends are distinguished here:

The head of state, time and time again, takes advantage of the shortcomings of the Constitution to reject even those draft laws that were adopted by the constitutional majority (as of 10 April — 52% of such cases).

Most of the unsigned law drafts come from the pro-presidential faction, which indicates weak communication between the President and his party and calls into question the very existence of the single-party majority.

The reasons behind the decisions not to sign are unclear: government officials initiate most draft laws, and only the President himself can say why he did not sign them.

What is the reason for the President to ignore draft laws?

A non-solid attitude towards statutory prescriptions that regulate the course of law-making is characteristic of the work not only of the President but also of the Parliament. In the Verkhovna Rada, violations during the adoption of draft laws have already become a common practice. Increasingly, legislators perceive the Rules of Procedures not as a set of rules but as a list of completely optional recommendations. After the full-scale invasion, two out of three laws passed have some sort of procedural flaw, and in 2021, Ruslan Stefanchuk noted that “in this Verkhovna Rada… not a single law of Ukraine was adopted in full accordance with the Rules of Procedures of the Verkhovna Rada”. In light of this, the library of unsigned draft laws at the Presidential Office no longer seems to be something incredible.

What is the President’s motivation for ignoring certain bills? Several hypotheses can be put forward:

- Some part of the draft laws, especially those adopted by the Verkhovna Rada at the beginning of martial law, has simply lost their relevance. An example is draft law No. 7153. Like some other law drafts, it was voted on at the beginning of the full-scale invasion, when circumstances constantly changed. After the liberation of a large part of the north of Ukraine, many problems that the draft law was supposed to solve have lost their relevance. Therefore, the draft law’s obsolescence may be one reason for not signing it.

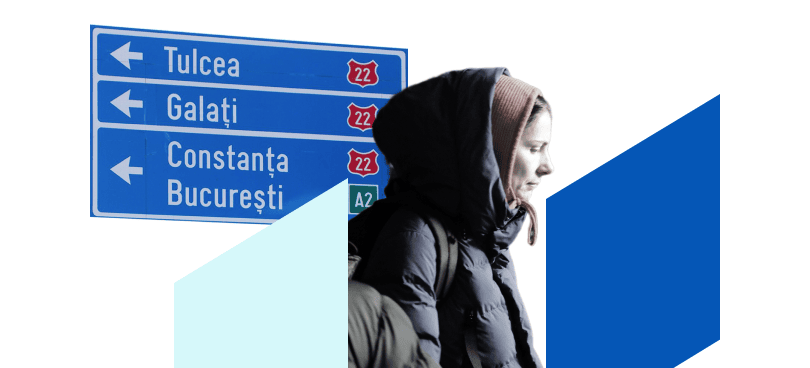

- The case of draft law No. 5655 On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine on Reforming the Field of Urban Development is illustrative. It received a lot of criticism, including from the Union of Architects and civil society. Even more: the European Parliament directly stated that adopting this draft law is an obstacle to the EU. Yet it was supported by the majority of votes in the Verkhovna Rada, so the President should have signed or vetoed the law. Still, vociferous fallout seems to have done its job, so the guarantor of the Ukrainian Constitution is not ready to sign it. Then why not use the right to veto? Here comes the time for speculation: conflict of interest? Reluctance to push back lobbyists? In each case, vetoing or signing is a loud message to the concerned groups. It is less provocative to leave the document until better times.

How to go about this?

What are the ways to change the current situation? Solving this problem is a complex issue. The thing is that the said imprecision in the Constitution becomes obvious to the public only after the news about another unsigned draft law. This happened both with draft law No. 2689 On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine regarding the Implementation of International Criminal and Humanitarian Law in 2021 and, more recently, with the scandalous draft law No. 5655. Every now and then, a small piece of the Constitution gives rise to scandals, rallies and heated discussions, and each time only the President is accused of not wanting to do something with a given draft law. With time and further regular law violations, the systematic problem of the disproportionate power of the head of state may come to the fore. Yet, at present, it is possible to observe a reaction to just piecemeal symptoms but not to the source of the disease.

The lack of a diagnosis as such is the worst part of the whole situation. Should he wish to do so, the President may stop the work of the entire state machinery by simply not letting anything whatsoever reach Holos Ukrayiny (Voice of Ukraine, an official herald). In retrospect, it can be seen how the head of state abuses this imprecision of the Constitution increasingly more, turning a blind eye to an inconvenient draft law at the right moment. No one can control this, as there is no system of checks and balances in this regard. This is the most alarming red flag of all those noted earlier.

But in addition to the public, there is another group of people for whom the status quo is not beneficial. These are MPs themselves. Ultimately, it is they that suffer most from such arbitrariness of the President. The entire outcome of their work can be crossed out by being ignored — and what if the most important draft law of the opposition party or even the coalition itself is sent to purgatory in the Presidential Office?

Maybe the Constitutional Court has a solution? It repeatedly issued interpretations of Article 94 of the Constitution — in 1997, 1998, and 2008. But there is no answer to the question of what to do when the President does not sign laws. Instead, its decisions concernув the method of calculating days (15 calendar or working days), the peculiarities of submitting proposals and imposing vetoes, signing laws adopted in referendums and the entry into force of the Constitution. Naturally, even under martial law, a group of MPs can turn to the Constitutional Court and ask it to explain the provisions of the Basic Law. However, the court may refuse to address this issue. For example, in 2008, concerning another problem, the court noted that “the procedure for signing and promulgating laws adopted by an all-Ukrainian referendum is not regulated in the Constitution of Ukraine. This issue is exclusively for the legislative body and does not belong to the competence of the Constitutional Court of Ukraine”.

It is quite doubtful that the court will construe Article 94 so that it is the Speaker of the Verkhovna Rada who must sign draft laws not signed by the President. After all, such norms are not written directly and clearly. Should the court interpret insufficient regulation so that the President him/herself must sign draft laws that have not been signed before, the verdict will not change the situation: the President is acting this way now. The systemic problem remains the ability of the President to completely block the process of adopting laws that s/he does not like and the inability of the Verkhovna Rada to resolve this situation even if more than 300 MPs wish to do so.

Thus, the most realistic way to solve the problem is to amend the Constitution. This is important, at least for MPs themselves, because their own gains will then be guaranteed. And taking into account the fact that the Rules of Procedure of the Verkhovna Rada have not been considered as something mandatory for a long time, a comprehensive reform suggests itself. But this should really be the position of the majority — after all, an amendment to the Constitution needs the votes of more than 300 lawmakers.

Still, it must be noted that the Constitution’s changes should be expected after the war, as the Basic Law may not be amended under martial law. This, of course, does not mean that the mentioned reform is not overdue, and public discussions are extremely needed. Although currently, no one from MPs’ chambers articulates the need for specific reforms, there is hope for change, not least thanks to the infamous law draft No. 5655.